Are zoos ready to face their historical mistakes?

Stepping into the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, a zoo with over two centuries of history, you’re met not with a cheerful atmosphere, but with the solemn aura of a living monument.

La fauverie, an elegant Art Deco structure renovated by René Berger in 1937, houses endangered cats like the snow leopards and Chinese leopards. Above its entrance hangs a beautiful frieze depicting hunters triumphantly conquering large wild cats. This striking artwork feels out of place amidst today’s emphasis on conservation and animal welfare. Yet, instead of removing these outdated symbols, the zoo has chosen to preserve them, turning these relics into powerful reminders of our cultural history and a point of reflection.

La fauverie

Inside la fauverie

Baby snow leopard in la fauverie

The Architectures of Control

The Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes is the world’s first public zoo. Compared to today’s zoos, it feels more like a garden with living museums. Its design followed the scientific mindset of those centuries, meticulously categorizing animals by species. Housing big cats, monkeys, birds, and reptiles in separate pavilions, rather than grouping them by ecological habitats.

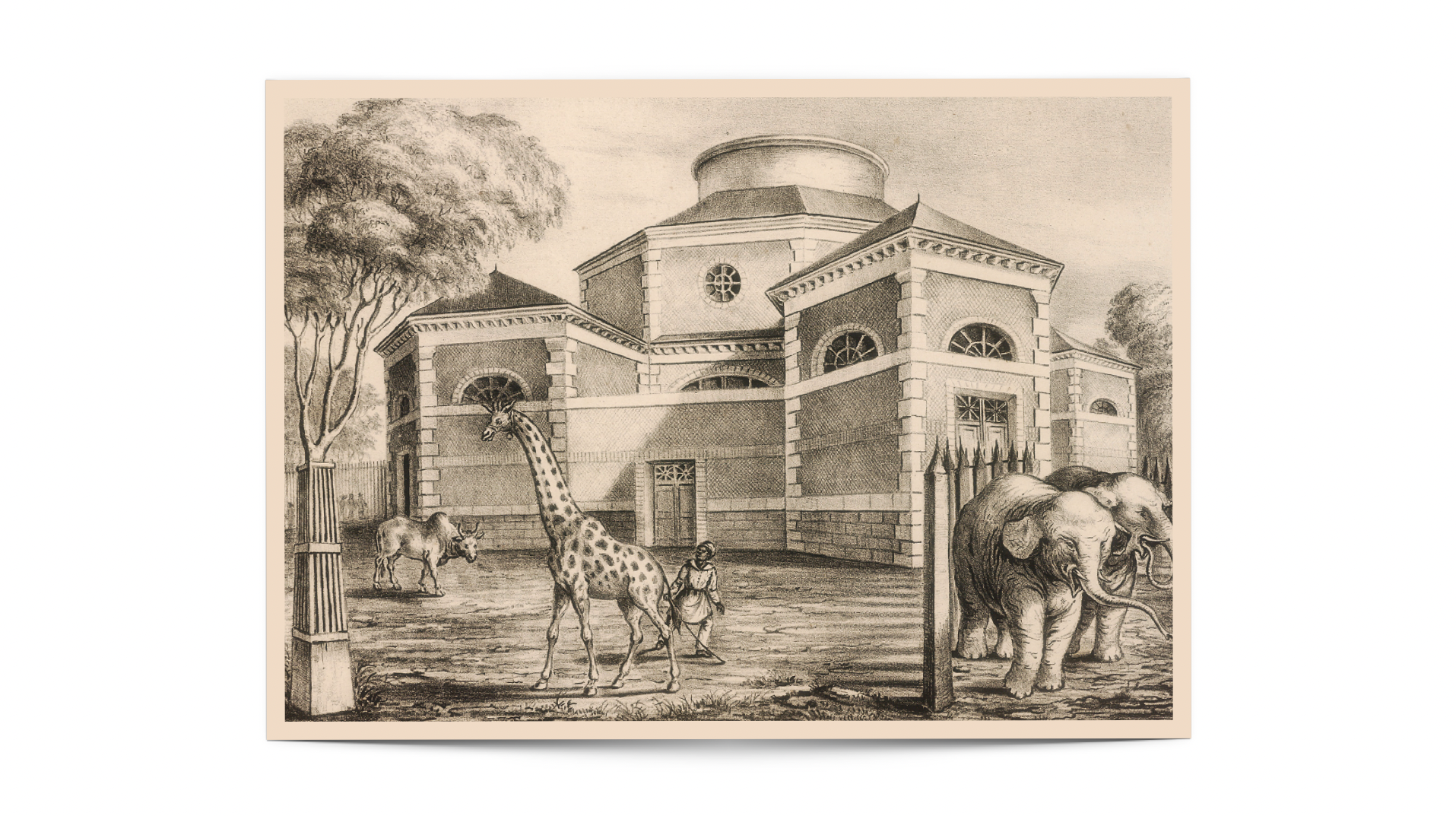

One of the zoo’s most iconic buildings is the Rotonde, originally built to house elephants and other large mammals. From a modern perspective, the space is clearly inadequate for such animals. Today, the Rotonde has been adapted for smaller species like tortoises. Outside, bronze statues of former residents serve as silent witnesses, reminding us of a time when humanity misunderstood animal welfare.

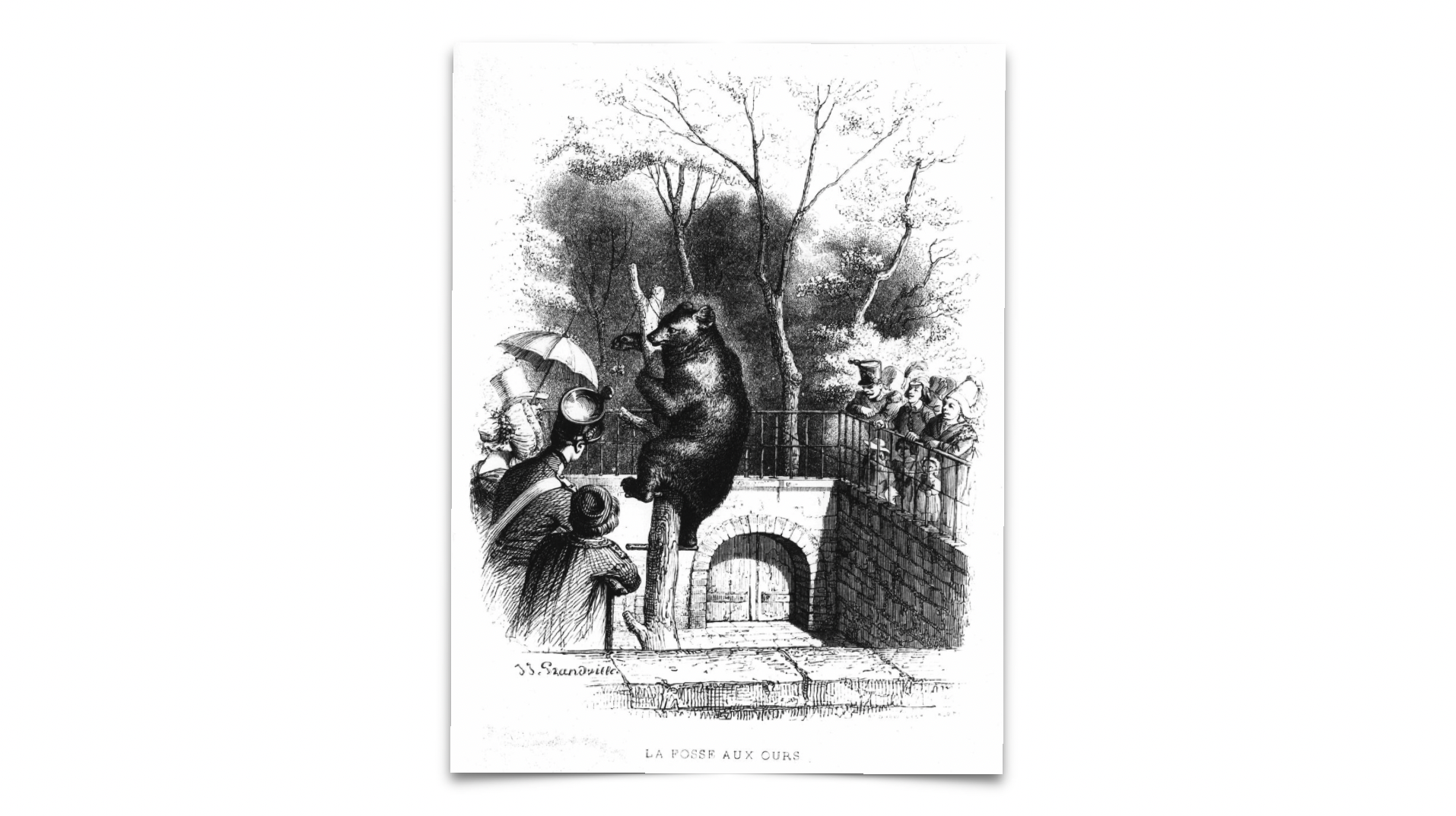

Nearby, two pits that once confined bears have been transformed into habitats for red pandas and binturongs, the small, tree-dwelling mammals. These enclosures were originally designed for visitors to look down upon the animals, a practice now recognized as psychologically stressful for animals and reflective of outdated, hierarchical human attitudes. By choosing smaller arboreal species and designing climbing structures that allow them to meet visitors at eye level or higher, the space has been reimagined to promote more natural and enriching environments.

In its earliest days, the zoo exemplified the scientific pursuit of order and classification. Animals were housed like living specimens, each enclosed in their own architectural "display cabinets." These structures reflected a time when humans sought to dominate and categorize nature, often without fully understanding it.

The Rotonde

Art of the Rotonde

Binturong living in the historic bear pit

Art of bear pit

Spectacle of Colonial and Natural

The history of Paris’s cultural buildings also reveals this mindset of dominance. The Palais de la Porte Dorée, built initially for the 1931 Paris Colonial Exhibition, still stands as a grand example. Its monumental façade is adorned with elaborate relief sculptures, placing France at the center of a vast colonial empire. In its basement, the Aquarium Tropical showcased exotic aquatic life from France’s overseas colonies. An imperial exhibition of nature, intended to dazzle and affirm colonial power.

In 1934, inspired by the Colonial Exhibition, another zoo was established in Paris. Parc Zoologique de Paris moved away from rigid scientific classifications, instead presenting animals within immersive biogeographic zones. Its towering artificial rock formation, a symbol of nature’s grandeur, embodied a shift from conquest to admiration, though not yet fully embracing conservation ideals.

Palais de la Porte Dorée

Parc Zoologique de Paris

From Spectacle to Reflection

Today, across Europe, legal protections for historical buildings often prevent significant alterations. Designers working on the immersion dreams taken back from American theme parks and zoos within these "architectural shells" can't always integrate modern exhibition concepts with historical structures. Some attempt to conceal outdated elements with new thematic designs, like jungle expeditions, often resulting in a jarring disconnect between setting and content.

Paris offers a different approach. Rather than conceal the past, it openly acknowledges the context of the relationship between Parisians and nature. Exhibits explain why certain structures exist, why animals were displayed in specific ways, and how our understanding of nature has evolved. The outdated hunter’s relief above la fauverie remains, not as a celebration, but as a visual testament to a history we must learn from.

In Paris’s zoos and aquariums, the layered history of scientific discovery, colonial exhibition, nature worship, and the emergence of conservation values unfolds before us. Preserving these historical monuments does more than protect architecture, it safeguards the collective memory of a city. And what we so often accept as "truth" is nothing more than a reflection of our time. One can only hope that when future generations look back on the zoos of our era, they will be better equipped to recognize and confront the historical mistakes we continue to make today.